|

Download as PDF

Written Statement for the Record

Of

Aisha Pittman

Senior Vice President of Government Affairs,

The National Association of ACOs

For the

House Energy and Commerce Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee

Hearing on

“MACRA Checkup: Assessing Implementation and Challenges That Remain for Patients and Doctors”

June 22, 2023

Chairman Griffith, Ranking Member Castor, and members of the subcommittee, my name is Aisha Pittman, and I am the Senior Vice President of Government Affairs at the National Association of ACOs (NAACOS). Our association represents more than 400 accountable care organizations (ACOs) in Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurance working on behalf of health systems and physician provider organizations across the nation to improve quality of care for patients and reduce health care costs. NAACOS members serve over 8 million beneficiaries in Medicare value-based payment models, including the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) and the ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model, among other alternative payment models (APMs).

We applaud the subcommittee for holding this hearing to discuss implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA). For years doctors, hospitals, and other providers have been paid for each service provided — a system commonly referred to as fee-for-service (FFS). Over the last two decades, innovative providers and policymakers have increasingly recognized the need to transition to alternative systems that reward accountability and create incentives for providing care in a coordinated manner focused around placing people at the center of their care and keeping them healthy.

MACRA’s Successes

To this end, Congress passed MACRA in 2015 to eliminate Medicare’s sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula, establish unified quality reporting systems, and provide financial incentives for clinicians to join APMs. A key aim of MACRA was to shift how Medicare pays for health care services to encourage keeping patients healthy and out of the hospital, reducing unnecessary care, and lowering costs for both patients and taxpayers.

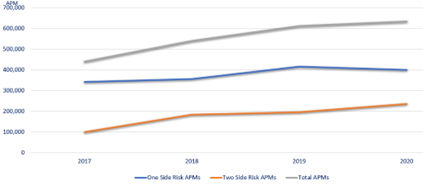

MACRA’s value-based payment reforms are rooted in the principles of accountability where financial performance is linked to quality rather than volume. To help achieve this important goal, MACRA provided 5 percent incentive payments to facilitate participation in advanced APMs, models that incorporate a level of downside risk for providers. Since MACRA became law in 2015, these incentive payments have helped grow participation in APMs. Between 2017 and 2020, Medicare saw a nearly 60 percent increase in the total number of clinicians participating in APMs (Appendix A).[i] Additionally, MACRA’s incentives helped increase participation in advanced APMs, which incorporate downside risk. In 2021, there were 271,000 clinicians that qualified as advanced APM participants, a 15 percent increase from the previous year.[ii] More importantly, since 2017 the growth of advanced APMs has increased by nearly 173 percent.

MACRA’s incentive payments not only encourage physicians and other health care providers to enter models but also provide additional resources that can be used to expand services beyond traditional FFS. ACOs, which account for over 90 percent of Medicare’s advanced APMs,[iii] have used these incentive payments to reinvest in patient care, fund wellness programs, fund patient transportation and meals, hire patient care navigators, and retain staff. MACRA’s incentive payments help provide services that are not typically reimbursed through Medicare but improve patient health outcomes and wellbeing. For example, UnityPoint in Iowa utilizes care management visits following an inpatient stay to allow clinicians to better manage the patient’s medications, assess their home for safety risks, and coordinate follow up care. As a result, Unity Point is able to reduce readmissions and ensure that patients’ needs are met at home.

Today, ACOs are the largest and most successful model leading this value-based care transformation. In 2023, there are 588 ACOs coordinating care for 13 million Medicare beneficiaries.[iv] ACOs are a voluntary alternative to the fragmented FFS system that gives doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers the flexibility to innovate care and holds them accountable for the clinical outcomes and cost of treating an entire population of patients.

With primary care as the backbone, ACOs employ a team-based approach that allows clinicians to ensure patients receive high quality care in the right setting at the right time. The ACO model also provides an opportunity for providers to work collaboratively along the continuum while remaining independent. Importantly, ACOs provide shared savings opportunities and enhanced regulatory flexibility that allows clinicians to maintain financial security while practicing medicine more freely.

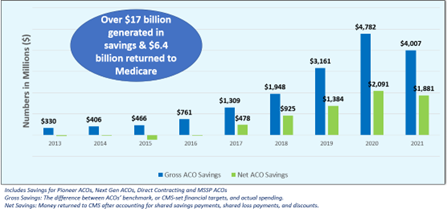

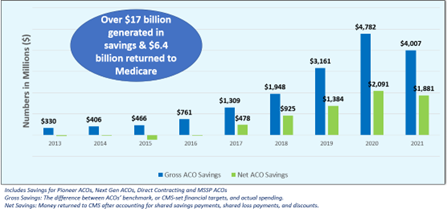

It’s clear these payment system reforms have been a good financial investment for the government. In the last decade, ACOs have generated more than $17 billion in savings with $6.4 billion being returned to the Medicare Trust Fund while maintaining high quality scores for their patients (Appendix B). The growth of APMs has also produced a “spill-over” effect on care delivery across the nation, slowing the overall rate of growth of health care spending. Earlier this year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reported that actual Medicare and Medicaid spending between 2010–2020 was 9 percent lower than original projections.[v] While there are several influences for these changes in spending, improved care management and more efficient use of technology were factors highlighted by CBO.

Challenges of MACRA

While advanced APMs are transforming how patients in traditional Medicare receive care, the ability for clinicians to qualify for the incentive payments is set to expire at end of 2023. In December 2022, Congress passed a pared down, one-year (3.5 percent) extension of MACRA’s incentive payments. If Congress allows these incentive payments to expire before making broader reforms to MACRA, it will have a chilling effect on participation in models that have seen growing uptake in recent years. When MACRA became law, CMS estimated that the share of Medicare physician dollars in APMs would increase to 60 percent in 2019 and to 100 percent by 2038.[vi] Unfortunately, uptake of these models has been slower than originally projected. In the President’s Fiscal Year 2024 budget, CMS indicates that roughly 25 percent of Medicare payments were tied to APMs incorporating downside risk in 2021.[vii] Several factors have contributed to slower growth in advanced APMs:

- Incentives favor the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Total maximum potential incentives permitted under MIPS are 9 percent, which is greater than the incentive payments for advanced APMs. While MIPS adjustments have averaged about 2–3 percent in recent years, the incentives in MACRA are misaligned. Additionally, if the incentive payments for advanced APMs are allowed to expire, the 0.75 percent conversion factor update in MACRA will not be enough of a financial incentive to keep some clinicians from moving back to MIPS where they can earn a 0.25 percent payment update and also qualify for bonuses of up to 9 percent. In the 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, CMS also highlights that MACRA incentives for advanced APMs are not expected to catch up to maximum MIPS bonuses until after 2038.[viii]

- Participants in APMs are often still subject to MIPS. Clinicians in non-risk bearing APMs or advanced APMs that do not meet qualifying APM participant (QP) thresholds for incentive payments remain in MIPS. This creates an additional burden as the clinicians must be responsible for MIPS quality reporting obligations and quality reporting obligations in the APM as well. This creates a disincentive to participate in APMs and holds FFS as the gold standard, rather than value-based payment.

- Moving too quickly to digital quality reporting will increase costs and burdens. ACOs will be required to report quality via electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs) or MIPS CQMs by 2025. While ACOs ultimately want to achieve a more seamless, efficient, and technology-enabled quality reporting system that is highly interoperable and relies on near real-time data to enable improved patient care, the current lack of interoperability means ACOs will face many challenges and increased administrative burden and costs to try and support this work in the near term.

- Limited payment models. While CMS’ population health models have seen sizable growth in the last 10 years, there have been limited participation options for all types of providers. Additionally, the broad set of past models often conflicted with one another making it difficult for clinicians to participate. In the last few years, the administration has set a goal to have all Medicare beneficiaries in an accountable care relationship by 2030. To achieve this goal, a more streamlined approach is necessary that builds upon successful models to establish viable participation options for more types of providers.

- Inability for some providers to move to risk. Providers vary in their ability to take on downside risk. While we have seen more Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), Rural Health Clinics (RHCs), and Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) joining value-based care models, adoption has been slowed by several underlying issues. Specifically, a focus for rural providers is retaining access to care. Approaches that require savings to Medicare through discounts or shared savings may not be appropriate for providers who are paid at cost or are struggling to remain open. Additionally, we know that all providers need time and significant investment to move to risk. Successful transition to advanced APMs has a high cost to providers that can average $1–2 million per year depending on an organization’s size.

- Thresholds to qualify as an advanced APM are too high under current law. In the 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule, CMS estimated that 80,000–100,000 clinicians may no longer qualify as advanced APM participants because of increasing qualification thresholds and expiring incentives.[ix] Additionally, the thresholds are calculated in a way that can make including specialists in population health models more difficult.

While MACRA was a step in the right direction, more needs to be done to drive long-term system transformation. Lawmakers must work to stabilize Medicare’s payment system. This means ensuring payment adequacy for providers is paired with appropriate financial incentives and regulatory flexibility that will encourage more participation in payment models where the value of care provided is rewarded over traditional volume-based care.

EXTENSION OF CURRENT INCENTIVES

Overall, MACRA’s incentives have driven change in the Medicare payment system, but the incentive structure needs to be revisited for growth to continue. It’s clear that advanced APMs are transforming how patients in traditional Medicare receive care, but uptake has been slower than originally projected. In the short-term, Congress can maintain MACRA’s progress by passing a multi-year extension of MACRA’s original 5 percent advanced APM incentive payments and giving CMS the ability to set qualification thresholds.

MACRA’s 5 percent advanced APM incentive payments help drive growth in risk-based models, which save Medicare money and provide additional services for patients. In 2023, roughly 75 percent of ACOs are now in risk-based payment arrangements. These ACOs also generate almost 36 percent higher net per-beneficiary savings. If MACRA’s incentives expire this year and qualifying thresholds increase to unattainable levels, there will be a significant reduction in the move to value. Increasing thresholds and expiring incentives could result in a 32–42 percent drop in participation. Given the savings advanced APM ACOs have generated in recent years, a shift back to FFS for these clinicians could possibly increase total Medicare spending annually.

FUTURE FINANCIAL INCENTIVES

Basis Principles for Revising Incentives

While MACRA’s incentive structure was designed to encourage movement to value, we have learned that the current incentive structure is complex and does not always favor value, as noted above. Most notably, Congress should start by revising MACRA’s Quality Payment Program (QPP) to develop a three-tier system that provides increased flexibility and financial incentives for the adoption of value. The participation tracks should be:

- Fee-for-service (MIPS)—Clinicians that are not participating in any APM. MIPS should be revised so that the program does not incent remaining in FFS. Specifically, Congress should structure MIPS to have adequate payment adjustments for physicians but no additional incentives unless clinicians are taking steps to move to value.

- APMs—Clinicians participating in ACOs or other APMs that hold them accountable for cost and quality. Clinicians in this track should be exempt from MIPS quality reporting and only held to the quality and payment parameters of their model. Financial incentives should recognize the up front and ongoing investments needed to be successful in APMs.

- Advanced APMs—Clinicians participating in risk-based models. This track should have the strongest financial incentives and flexibility.

Additionally, new approaches should focus on simplifying the incentive structure to help providers more easily weigh the costs and benefits of the progression to value. Incentives and payment model structure must also account for providers serving rural and underserved populations. Specifically, incentive payments and model flexibility should consider the services needed and costs of addressing social determinants of health (SDOH) and health-related social needs (HRSNs) for rural and underserved populations. Ultimately, the incentive structure and payment models should be decoupled from FFS over time. Increasing participation in value-based payment arrangements will (1) require a new approach for determining payment as FFS will no longer be a sufficient reference population and (2) reduce the need for archaic FFS rules aimed at preventing waste.

Conversion Factor

Beginning in Performance Year 2024, clinicians will be eligible to receive 0.75 percent conversion factor updates for qualifying as an advanced APM participant. Under MACRA’s current incentive structure, this might not be enough of an incentive for providers to move into Medicare’s more advanced risk-based models. CMS expressed concern in the 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule that the substantial difference between the QP conversion factor and maximum positive payment adjustment available under MIPS might affect the willingness of eligible clinicians to participate in advanced APMs for several years to come. If this happens, it could also impact the availability and distribution of funds in the budget neutral MIPS payment pool as more high-performing clinicians choose MIPS over advanced APMs. Moreover, the current structure does not account for inflation and could result in inadequately paying providers as costs rise. A three-tiered payment system should account for inflation in payment updates and maintain incentives for moving to value by providing higher updates for APMs and advanced APMs.

It’s also critical that Congress includes safeguards to ensure that payment updates for all types of APMs do not negatively impact their financial performance in their models. For example, under current law when advanced APMs receive a higher conversion factor update, it will be more difficult for the advanced APM to reduce spending below benchmarks. This is because APM benchmarks are based on national and regional spending trends. If most providers are still under FFS, the benchmarks will be reflective of the lower payment update. Congress should direct CMS to ensure that benchmarks are not penalizing APMs for an incentive structure designed to encourage value.

Bonuses and Incentive Payments

With only 25 percent of clinicians in value models that incorporate downside risk, robust financial incentives are still needed to grow APM participation. Beyond an initial short-term extension of MACRA’s incentives, Congress should consider a more sustainable longer-term incentive payments system that helps clinicians move away from standard FFS. To successfully transition to value-based care models, clinicians must invest in workflow improvements, digital health tools, care coordinators, data analytics, quality measurement systems, transitional care services, and innovative patient engagement methods.

While these advanced care delivery tools help improve patient care and outcomes, they have a cost. Incentive payments have been critical in helping clinicians make these initial investments and continue reinvesting in these care transformation initiatives that benefit patients. MACRA’s payment system reforms and financial incentives have helped drive this care transformation. Going forward, Congress should use incentives as the building blocks to care transformation and consider the following:

- Extend and increase the percentage of incentive payments for new participants and clinicians serving rural and underserved communities. Participation in risk-based models has been well below original projections, and more robust incentives will help draw more clinicians into models. Incentive payments could also be slowly phased down or adjusted over time once participation in APMs reaches pre-determined thresholds.

- Align the qualification year with the year in which incentive payment amounts are calculated. The current two-year lag in payments is a disincentive.

- Establish a permanent high-performance bonus program that is funded using APM savings returned to Medicare. ACOs save Medicare billions of dollars. High performance bonuses could be limited to advanced APMs or expanded to all APMs with a sliding scale for payments.

APM Qualification Thresholds

MACRA’s current qualification thresholds are based on the individual providers in the APM. This approach has several limitations that make it difficult for some ACOs to qualify. The current QP thresholds can also make it difficult for some ACOs to include specialists, CAHs, RHCs or FQHCs. To qualify, clinicians must receive a certain percentage of Medicare Part B payments or see a certain percentage of Medicare patients through an the APM entity. These percentages have increased since MACRA became law and will again at the end of 2023. Additionally, these thresholds can also increase operational and administrative burdens on APM entities. Under the current system, entities need to be experts in both MIPS reporting and advanced APM regulations. This can be difficult for ACOs that are managing hundreds or thousands of clinicians across multiple practices or hospital systems.

Going forward, Congress should consider eliminating QP thresholds altogether or varying the thresholds based on purpose. For example, thresholds could be eliminated for payment updates, while maintaining thresholds for qualifying for bonuses. Either way, if thresholds are maintained, Congress must give the administration more flexibility to adjust thresholds through rulemaking. This will allow qualifying thresholds to account for model type, provider type, and current APM adoption.

NON-FINANCIAL INCENTIVES AND MODEL FLEXIBILITY

MSSP Enhanced Plus

The MSSP is the largest and most successful value-based care program in Medicare and as such should be utilized as an innovation platform. As the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) tests new payment models, successful models or key aspects of those models should be embedded as permanent parts of Medicare via the MSSP. The MSSP currently includes various participation options with increasing levels of risk and reward, including Basic Track Levels A–E and the Enhanced Track. However, there is currently no full-risk option for ACOs participating in MSSP, with the highest level of risk at 75 percent of shared savings/losses under the Enhanced Track.

Congress should direct CMS to create a separate full-risk option within MSSP to serve as a better bridge between it and ACO REACH. This “Enhanced Plus” track should include greater flexibility in payment design and available waivers. Elements of an “Enhanced Plus” option should include:

- Full risk, i.e., 100 percent shared savings and loss rates,

- Participation at the Tax ID Number-National Provider Identifier (TIN-NPI) level to allow the ACO to create a high-performing network, which is critical for such a high-risk model,

- Options for population-based payments ranging from partial to full capitation with the ability to negotiate downstream value-based payment arrangements, and

- Advanced waivers including the Post Discharge Home Visit Waiver, Care Management Home Visit Waiver, and tailored Part B cost sharing support.

As the only permanent total cost of care model in Medicare, the MSSP should be adapted to remain a viable option for more advanced ACOs and further advance value-based care.

Population-Based Payments for Primary Care

At a minimum, Congress should direct CMS to create an option for MSSP ACOs to elect partial or full capitated payments for primary care. Hybrid payment systems that include both FFS payments and capitated/population-based payments (PBPs) have gained traction, particularly among the primary care community. Additionally, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)’s 2021 report recommended a shift to a hybrid payment model to better support robust primary care.[x] Such PBPs would allow ACOs to reallocate resources to advance primary care innovation and transformation. This voluntary payment option should include flexibility for providers to select capitation levels that meet their needs. Given the critical role of primary care in improving quality and controlling costs, implementing a hybrid payment option within the MSSP could be an effective strategy in furthering the transition to value.

Waivers

Current law allows CMS to waive certain Medicare FFS requirements in MSSP and other APMs. This is a critical component of APMs as it allows providers to operate with fewer restrictions leading to a reduction in provider burden and increased care innovation. However, the waivers to date have been limited, are burdensome, and are limited to a few models. For example, MSSP only has waivers for telehealth and the 3-day rule for skilled nursing facility stays. Yet the ACO REACH model has access to many more waivers. We believe all APMs should have access to all available waivers and that those waivers shouldn’t be limited to certain models. Congress should direct CMS to establish a common set of waivers for APMs.

Similar to financial incentives, a standard set of waivers for risk-bearing APMs should decouple ACOs and other APMs from FFS. Specific opportunities include:

- Addressing SDOH and HRSNs by allowing ACOs to pay for non-Medicare covered services.

- Allow ACOs to test innovations that are being tested outside of the model. For example, Medicare’s Hospital at Home waiver should be available to ACOs after the current two-year extension.

- Expand telehealth services for all ACOs regardless of risk level or choice of attribution. While some ACOs have access to telehealth waivers, the public health emergency (PHE) provided a more expansive set of waivers for all providers. Outside of the PHE, telehealth is limited to risk-bearing ACOs who select prospective alignment, even then only for their aligned patients. It’s infeasible for providers to only offer telehealth to such a limited portion of their patient populations. ACOs are accountable for the total cost of care and quality and thus incented to ensure patients get the right care in the right setting. This mitigates concerns with overuse of telehealth or stinting care that may be present in FFS. Additionally, Congress should provide protections for ACOs using retrospective assignment, who are acting in good faith and provide telehealth to a beneficiary that does not eventually align to the ACO.

- Improve the MSSP Beneficiary Incentive Program (BIP). Congress created a beneficiary incentive program for MSSP in 2018’s Bipartisan Budget Act that allows ACOs to provide beneficiaries who receive primary care services up to $20. While well intentioned, this program has not been used because it lacks flexibility to tailor the program. Congress should make technical corrections to the statute to give ACOs flexibility to establish BIPs that are based on the needs of their populations. For example, ACOs could limit the incentive program to certain high-cost or high-need patients and/or for a discrete set of services.

Driving Innovation in Medicare Advantage (MA)

Recognizing ACOs’ and MA’s shared goals of improving the quality of care and cost savings to patients, it’s imperative to build parity between the two programs. Misaligned incentives are harmful to advancing value as they increase provider burden, create confusion and disincentives for patients, and generate market distortions that favor one entity over another. Parity can be better provided in the programs’ benchmark and risk adjustment policies, quality measurement, and marketing requirements. ACOs should be allowed to provide comparable benefits to those offered to MA patients, such as telehealth visits, transportation benefits, home visits, etc. Without parity, providers are forced to spend time managing to the various program requirements rather than managing patient care. For example, when addressing SDOH, providers must consider the patients’ Medicare eligibility. Providers are better equipped to address SDOH for patients in MA because MA provides the opportunity to pay for services not covered by traditional Medicare.

Furthermore, Congress should encourage MA plans to enter risk-bearing arrangements with providers. Unfortunately, most of MA’s payments to providers are still rooted in FFS. This doesn’t encourage value-based care that we know helps manage chronic illnesses, provide preventive services, and keep patients healthy. MA should have explicit incentives that will encourage provider-led transformation. Incentives could be tied to the Star Ratings or rebate dollars. Additionally, Congress should require MA plans to share full patient data with providers. In existing risk-bearing arrangements in MA, providers often have limited data on the services received outside of their care. This hampers the ability to coordinate care across the continuum. This is further evidenced by the lack of use of the Other Payer Arrangements designation option to qualify for advanced APM incentive payments.

CMMI TRANSPARENCY

Develop a More Predictable Pathway for Additional Types of Clinicians to Engage in APMs

Congress established CMMI in 2010 to develop and test innovative payment and service delivery models. While population health models have seen encouraging growth over the last 10 years, there has been insufficient model development for all types of physicians and other clinicians.

CMMI has tested over 50 models, expanding our understanding of how to shift payment and care processes to improve patient outcomes. However, few models have met the criteria for expansion and lessons learned are not always translated into new models. Congress should work with CMMI to ensure that promising models have a more predictable pathway for being implemented and becoming permanent and are not cut short due to overly stringent criteria. In February, NAACOS and other stakeholders sent a letter to committee leaders outlining the following recommendations for improving CMMI, including:[xi]

- Broadening the criteria by which CMMI models qualify for Phase 2 expansion (e.g., does the model positively address health equity or effectively expand participation to more provider types).

- Directing CMMI to engage stakeholder perspectives during APM development, such as leveraging the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC).

Encourage Specialist Integration within Total Cost of Care Models

NAACOS supports the Administration’s goal of having all Medicare and most Medicaid patients in accountable care relationships by 2030. To successfully achieve this goal, policymakers must allow providers to coordinate care across the continuum of care. Over the last decade, we have learned that concurrent episode models and total cost of care models result in a complex set of overlapping rules. This leads to provider and patient confusion and increased burden. Designing specialty payment approaches within a total cost of care arrangement can create the proper incentives to encourage coordinated care across the care continuum. In April, NAACOS responded to a request for information from the PTAC encouraging CMS to work with ACOs on the following priorities, including:[xii]

- Sharing data on cost and quality performance for specialists with ACOs.

- Supporting total cost of care ACOs with voluntary shadow or nested bundled payments for those who elect these arrangements.

- Addressing policy and program design elements that currently are prohibitive to this work.

CONCLUSION

Thank you for this opportunity to appear before the subcommittee to discuss ways to improve MACRA. Our members are committed to providing the highest quality care for patients while advancing population health goals for the communities they serve. We look forward to your continued engagement to improve the Medicare payment system.

APPENDIX AND CITATIONS

Appendix A: APM Growth Since Passage of MACRA

Appendix B: ACO Savings 2013–2021

[i] CMS Quality Payment Program Experience Reports (2017; 2018; 2019; 2020): https://qpp.cms.gov/resources/resource-library

[ii] CMS QPP Report (2021): https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2433/2021%20QPP%20Experience%20Report.pdf

MedPac Data Book (2022): https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/July2022_MedPAC_DataBook_Sec5_SEC.pdf

[iv] NAACOS (2023): https://www.naacos.com/press-release--medicare-aco-participation-grows-in-2023

[v] CBO Projections of Federal Health Care Spending (2023): https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-03/58997-Whitehouse.pdf

[vi] CMS Estimated Effects of MACRA (2015): https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/research/actuarialstudies/downloads/2015hr2a.pdf

[vii] CMS Budget Justification (2024): https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-fy-2024-congressional-justification-estimates-appropriations-committees.pdf-0

[viii] Federal Register: CMS Physician Fee Schedule (2022): https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-07-29/pdf/2022-14562.pdf

[ix] Federal Register: CMS Physician Fee Schedule (2022): https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-07-29/pdf/2022-14562.pdf

[x] NASM Report on Primary Care (2021): https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/25983/High%20Quality%20Primary%20Care%20Policy%20Brief%201%20Payment.pdf

[xi] ACO Stakeholder Letter to Congressional Leaders (2023): https://www.naacos.com/assets/docs/pdf/2023/118thCongressValue-BasedCareRecsCoalitionLetter.pdf

[xii] NAACOS RFI Comments to PTAC on Specialty Engagement (2023): https://www.naacos.com/assets/docs/pdf/2023/FinalPTACSpecialtyEngagementRFIComments040623v2.pdf

|