|

Download as PDF

September 6, 2022

The Honorable Chiquita Brooks-LaSure

Administrator

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Attention: CMS-1770-P

Submitted electronically to: https://www.regulations.gov/commenton/CMS-2022-0113-1871

RE: Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2023 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; etc.

Dear Administrator Brooks-LaSure:

The National Association of ACOs (NAACOS) appreciates the opportunity to submit comments in response to the CY 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) proposed rule. NAACOS represents more than 400 accountable care organizations (ACOs) serving over 13 million beneficiaries through a variety of value-based payment and delivery models in Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurers. Our ACO members participate in Medicare models including the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) and the Global and Professional Direct Contracting Model (GPDC), among other alternative payment models (APMs). We appreciate that many of the proposed changes in this rule are responsive to recommendations we have made for improving the MSSP. Ultimately, many of these proposals will help grow participation in ACOs and realize CMS’s stated goal to have all Medicare beneficiaries in a relationship with a provider who is responsible for quality and total cost of care. Additionally, these proposals will build on the current financial success of the program, saving Medicare more than $15 billion and yielding more than $650 million in shared savings to ACOs. We appreciate that CMS has thoughtfully considered how to improve the program, our comments below reflect concerns of our members and our shared goals to grow the ACO program and ensure that all Medicare beneficiaries are in a relationship accountable for quality and total cost of care by 2030.

SUMMARY OF KEY RECOMMENDATIONS

In response to MSSP proposals, NAACOS urges CMS to:

- Finalize, with slight modifications, proposals to provide advance shared savings payments to certain ACOs. CMS should revise eligibility requirements to include all ACOs addressing health equity and modify the calculation of the risk factors-based score to identify underserved beneficiaries more accurately.

- Finalize policies to provide additional time in upside-only models. NAACOS applauds CMS for making a more balanced and appropriate onramp to assuming risk. Making these changes will be a step in the right direction toward attracting new participants to the program after a plateau in growth following the finalization of Pathways to Success policies.

- Eliminate the high/low revenue approach to ensure all vulnerable providers (rural, safety net, FQHC, RHC, etc.) have a reasonable progression to risk.

- Finalize proposals to make the Enhanced Track optional for all ACOs.

- Finalize the inclusion of an additional, alternative quality performance standard, which is a more balanced approach to determining how quality scores contribute to shared savings opportunities for ACOs.

- Abandon the current timeline and strategy for requiring ACOs to report quality via eCQMs/MIPS CQMs and to report on all-payer data.

- Provide more transparency around MIPS quality performance category scores so that ACOs can determine what performance metrics they need to meet to be eligible for shared savings.

- Allow current ACOs to opt into certain financial changes beginning in 2024.

- Keep its current two-way benchmark trend adjustment, rather than its proposed policy, that uses a blend of national and regional spending, but with two changes:

- (1) use the USPCC as the national component of the trend adjustment, rather than observed national FFS spending and

- (2) remove ACO-assigned beneficiaries from the regional comparison group, negating the effect of ACOs’ savings on the regional trend.

- Put sufficient guardrails in place, if the agency finalizes the proposed three-way trend update, to protect ACOs who would see lower benchmarks because of the ACPT. Specifically, we recommend CMS set ACOs’ historic benchmark at the higher of the proposed three-way trend adjustment or the current two-way trend adjustment.

- Finalize the proposal to account for prior savings when an ACO is rebased under a new agreement period. When accounting for prior shared savings, CMS should consider using an ACO’s actual maximum shared savings rate to pro-rate the positive average per capita prior savings and modify the 5 percent national spending cap in certain circumstances.

- Finalize proposals to reduce the cap on negative regional adjustments from 5 percent of national per capita FFS spending to 1.5 percent.

- Finalize policy that applies risk score caps after accounting for demographic changes and support setting the cap at the aggregate level, rather than by enrollment type.

- Finalize proposals allowing some ACOs in the Basic Track to earn some shared savings even if they fail to meet or exceed the minimum savings rate but apply to all ACOs, including high revenue ACOs.

- Allow ACOs the opportunity to elect pre-pandemic years for benchmarks.

- Engage stakeholders throughout development of administrative benchmarks.

- Finalize proposals to revise marketing requirements, streamline the SNF 3-day rule waiver application process, and recognize ACOs structured as OHCAs for data sharing purposes, which will reduce unnecessary administrative burdens placed on ACOs.

- Eliminate the proposed follow-up beneficiary communication, which would cause significant burden and worsen beneficiary confusion.

In response to Quality Payment Program (QPP) and Medicare PFS payment policies, NAACOS urges CMS to:

- Continue to pay office-based physicians at the higher “non-facility” rate once the COVID-19 PHE expires, rather than the lower facility rate, which would be detrimental to the brick-and-mortar physician practices.

- Monitor the implementation of proposals to strengthen health care providers’ capacity to address behavioral health in a team-based approach to ensure adequate uptake.

- Continue to improve billing and payment for E/M services and finalize policies to align “Other” E/M services with office and outpatient E/M services.

- Finalize proposals to expand access to telehealth and behavioral health care in RHCs and FQHCs.

- Finalize the proposal to make the 8 percent minimum on the Generally Applicable Nominal risk standard permanent and clarify that APM requirements can be met through a single quality measure.

- Work with Congressional leaders to support an extension of the 5 percent Advanced APM incentive payments and use the agency’s authority to lower the QP threshold through the patient count method.

- Evaluate ACOs at the APM entity level as this approach treats the ACO as a whole and reinforces the ACO model and avoids fractures within the ACO.

MEDICARE SHARED SAVINGS PROGRAM

Advance Investment Payments

CMS proposes to provide advance shared savings payments, referred to as advance investment payments (AIPs) to certain MSSP ACOs, modeled after the successful ACO Investment Model (AIM). We applaud CMS’s recognition of the significant upfront resources required to form an ACO and transition to value-based care. NAACOS has long advocated for CMS to make upfront funding available to ACOs, which will further our shared goals of expanding access to accountable care and advancing efforts to address health equity. Considering these goals, we urge CMS to expand availability of AIPs to all ACOs working to combat inequities in our health system. We commend CMS’s commitment to supporting the provision of accountable care for underserved beneficiaries and recommend CMS finalize the proposal with modifications, as detailed below.

Eligibility

As proposed, CMS would limit eligibility for AIPs to new (not renewing or re-entering) ACOs designated as low revenue and inexperienced with performance-based risk Medicare ACO initiatives that have applied and are eligible to participate in any level of MSSP’s Basic Track. We strongly encourage CMS to expand the eligibility criteria to include more types of ACOs and more provider types so that more patients can benefit from these important investments. The proposed eligibility criteria are overly limiting and would exclude many Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), Rural Health Clinics (RHCs), Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs), and other crucial safety net providers from receiving AIPs as they are often designated as high revenue by CMS’s definition despite having limited access to capital to invest in ACO activities.

CMS has acknowledged the historic lack of access to health care in underserved communities. Given the reliance on historic fee-for-service (FFS) expenditures in MSSP financial methodologies, this significant unmet need has led to ACO benchmarks that do not accurately reflect the cost of addressing the complex medical and psycho-social needs of these beneficiaries. Many existing ACOs that are designated as experienced with performance-based risk or participating in the Enhanced Track still lack the significant resources and infrastructure necessary to meaningfully address patients’ social drivers of health (SDOH) and overcome longstanding inequities in our health system. For these ACOs, AIPs could be leveraged to enhance sociodemographic data collection, create targeted interventions to reduce health disparities, and develop relationships with community-based organizations (CBOs) to address social needs. We urge CMS to explore expanded eligibility criteria to increase the positive impact of AIPs on the Medicare program and ensure equitable access to accountable care for all beneficiaries.

Application Procedure and Contents

CMS proposes to conduct the application process for AIPs in conjunction with the annual MSSP application cycle, and ACOs would be required to submit supplemental application information sufficient for CMS to determine the ACO’s eligibility to receive AIPs. We support CMS’s proposal to embed the AIP application cycle within the existing MSSP application process. We encourage CMS to provide detailed guidance, such as frequently asked questions (FAQs) and sample application documents, to ensure ACOs have a clear understanding of the requirements for a satisfactory application. This should include templates, detailed examples, and other support for ACOs drafting spend plans. These materials should be made available with ample time for ACOs to ask clarifying questions and prepare application documents. Given the stated intention to bring new providers into the program, CMS should conduct outreach to inform providers of this opportunity and support them through the application processes for both MSSP and AIPs.

CMS proposes that the initial application cycle to apply for AIPs would be for a January 1, 2024, start date, noting that current or renewing ACOs would not be eligible to apply. This may cause many ACOs that have already applied to participate in MSSP for performance year (PY) 2023 to delay joining the program until PY 2024 in order to take advantage of beneficial policies such as AIPs, that are proposed to be limited to ACOs with a January 1, 2024, agreement start date. We strongly recommend CMS, at a minimum, provide an opportunity for new ACOs with agreement periods beginning on January 1, 2023, to submit supplemental application materials for AIPs during the first application cycle and, if approved, to receive AIPs for the second and third years of their agreement periods (PY 2024 and PY 2025). This would help mitigate the disincentive to join MSSP for PY 2023.

Use and Management of Payments

Unlike standard shared savings payments, CMS proposes to limit the use of AIPs to investments in three categories: increased staffing, health care provider infrastructure, and the provision of accountable care for underserved beneficiaries (including strategies to address SDOH). Given the broad examples of permitted uses CMS provides within these categories, NAACOS supports the proposal to require AIPs be spent within the specified categories. CMS also provides examples of prohibited uses of AIPs, specifying that performance bonuses or other provider salary augmentation would constitute a prohibited use of funds. The agency then states that performance bonuses tied to SDOH strategies or increased salaries for clinicians treating underserved beneficiaries would not be prohibited. This may cause confusion for ACOs about what constitutes a prohibited expense. CMS should clarify any explicit examples of prohibited uses and only identify categories of expenses as prohibited if all uses under said categories would be prohibited to avoid confusion. We ask that CMS provide detailed guidance, beyond the examples outlined in the proposed rule, on what expenditures fall under the permitted categories to ensure that ACOs have a clear understanding of what uses are and are not permitted.

CMS also proposes that ACOs receiving AIPs must maintain a separate account designated for AIPs to better enable CMS to monitor how AIPs are spent. We support this proposal and the proposal to revisit the permitted categories in future rulemaking if the agency finds that additional flexibilities or restrictions are necessary.

Advance Investment Payment Methodology

One-time Payment

CMS proposes to provide a one-time upfront payment of $250,000 for each ACO that meets eligibility criteria and is approved to receive AIPs, referencing that a similar payment of the same amount was provided to ACOs that participated in AIM. NAACOS strongly supports CMS’s proposal to provide an upfront one-time payment as part of the AIPs, and we recommend that CMS increase the amount of this payment. In addition to the $250,000 lump sum payment provided in AIM, participating ACOs also received a one-time per beneficiary payment, augmenting the total upfront funding based on ACO size. Given the rising health care costs, worsening of health disparities, and significant inflation we have seen in the years since AIM was implemented, it would be appropriate to increase the upfront payment amount from what was provided in AIM rather than reducing it. CMS notes it is considering alternative values for the one-time payment by varying the payment amount based on the number of and/or the risk factors of the ACO’s assigned beneficiaries. NAACOS recommends that CMS pursue this approach, with $250,000 as the minimum value for the upfront payment, adjusting the amount upward for ACOs with larger beneficiary populations and for those serving higher proportions of underserved beneficiaries. Many of the providers that CMS seeks to attract to participate in MSSP with AIPs are struggling with continuing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, provider burnout and staffing shortages, and other pressing challenges. These providers need strong incentives to be able to invest in practice transformation, form an ACO, and meaningfully engage in the value-based care movement. CMS should consider these factors and ensure the upfront component of AIPs is adequate to overcome the challenges providers face in transitioning to value-based care delivery.

Quarterly Payments

In addition to the one-time upfront payment, CMS proposes to provide quarterly payments, calculated per beneficiary as part of the AIPs. NAACOS supports this proposal and agrees that providing quarterly, rather than monthly or yearly payments, appropriately balances the need for ACOs to have sustainable, predictable funding while minimizing the cost and burden to CMS associated with calculating and administering the per beneficiary payments.

Timing of Quarterly Payment Calculations

CMS proposes to determine the value of an ACO’s upcoming quarterly payment prior to the start of the quarter based on the latest available assignment list in order to best reflect the attributes of the ACO’s assigned population. We agree that calculating the quarterly payment amounts prior to each quarter using the latest available assignment list is the appropriate strategy for ACOs that have selected preliminary prospective assignment with retrospective reconciliation, as this will capture changes to the ACOs’ assignment lists throughout the performance year. However, NAACOS recommends that CMS take a different approach for ACOs that have selected prospective assignment and instead calculate the quarterly payment amounts for these ACOs prior to the first quarter of the performance year. Given these ACOs will not experience changes to their assignment lists during the performance year, determining the quarterly amount at the start of the performance year would provide more predictability for these ACOs and ease administrative burden on CMS.

Cap on Per Beneficiary Payments

CMS proposes to calculate the quarterly payment amounts by summing the per beneficiary payments for up to 10,000 beneficiaries, based on the cap used in AIM to protect the Trust Fund. As proposed, the per beneficiary payment amounts would be determined by the risk factors-based scores for each beneficiary. We strongly support CMS’s proposal to calculate the payment amount for ACOs with greater than 10,000 beneficiaries based on the 10,000 beneficiaries with the highest risk factors-based scores. We appreciate CMS’s efforts to provide higher payment amounts to ACOs treating underserved beneficiaries and encourage the agency to finalize this policy as proposed. This method is much more appropriate than the alternative proposal to determine the payment amount based on the average risk factors-based score of the ACO’s beneficiaries, which would dilute the impact of the risk factors-based scores on payments for ACOs with greater than 10,000 beneficiaries.

NAACOS also supports CMS’s proposal to notify each ACO in writing of its determination of the amount of the quarterly AIP and provide a detailed report of the calculation. This provides appropriate transparency and ensures ACOs have a clear understanding of how their payments are calculated.

Quarterly Per Beneficiary Payment Amounts

On Table 42 in the proposed rule (reproduced below), CMS outlines the proposed per beneficiary payment amounts associated with beneficiaries’ risk factors-based scores.

|

Risk Factors-Based Score

|

1–24

|

25–34

|

35–44

|

45–54

|

55–64

|

65–74

|

75–84

|

85–100

|

|

Per beneficiary payment amount

|

$0

|

$20

|

$24

|

$28

|

$32

|

$36

|

$40

|

$45

|

NAACOS supports the proposed payment amounts as we believe they appropriately provide additional funding for ACOs treating beneficiaries with greater levels of need, and we encourage CMS to finalize the per beneficiary quarterly payment amounts as proposed.

Determining Beneficiaries’ Risk Factors-Based Scores

CMS proposes to vary the per beneficiary payment amounts based on a risk factors-based score that the agency would calculate for each beneficiary, based on a beneficiary’s dual eligibility status (DES) and the Area Derivation Index (ADI) national percentile rank of the beneficiary’s primary address. We appreciate that CMS proposes to use ADI national percentile rank in this score rather than using the relative ADI based on the assigned beneficiary population, as done in the ACO REACH model. However, the ADI national percentile rank is still limited in that it does not effectively capture disadvantaged populations in high-cost regions. Therefore, NAACOS recommends CMS explore using a regionally adjusted ADI rather than ADI national percentile rankings as proposed; additional details on this recommendation are included further in this letter. We understand that adequate data sources to inform health equity initiatives are currently limited, and we support CMS’s efforts to leverage available data to pursue equitable payment policies promptly and encourage CMS to incorporate more and better data as they become available.

In this section, CMS outlines several alternative proposals for determining beneficiaries’ risk factors-based scores. In the interest of taking the most encompassing approach and avoiding excluding beneficiaries with greater need from these higher payment amounts, NAACOS recommends CMS finalize the following approach to determining risk factors-based scores:

- If the beneficiary is dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, assign a risk factors-based score of 100.

- If the beneficiary receives a Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) from Medicare, assign a risk factors-based score of 100.

- If the beneficiary is not dually eligible and does not receive a Part D LIS, assign a risk factors-based score equal to the adjusted ADI of the census block group corresponding with the beneficiary's primary mailing address (1-100).

- If the beneficiary is not dually eligible and does not receive a Part D LIS but cannot be matched with the ADI due to insufficient data, impute a risk factors-based score of 50.

We believe this is the most comprehensive approach that CMS proposes and therefore recommend that CMS use these three factors (DES, LIS, and ADI) as the starting point for calculating risk factors-based scores. Including the Part D LIS in addition to DES helps capture more underserved beneficiaries in states that have not expanded Medicaid and would therefore have fewer beneficiaries with DES. NAACOS supports CMS’s proposal to determine a beneficiary’s DES based on whether the beneficiary had at least one month of dual enrollment within the 12-month window corresponding with the assignment window used for preliminary prospective assignment with retrospective reconciliation for that particular assignment run. We also support CMS’s proposal to impute a score of 50 out of 100 for those beneficiaries for which CMS does not have sufficient data to calculate a risk factors-based score and provide the median payment amount. While we support the concept of using Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) for primary care to inform the risk factors-based score, the approach as proposed by CMS would limit the refinement of the scores. NAACOS encourages CMS to explore alternate strategies for incorporating HPSA, as well as other metrics, into the score calculations.

As detailed elsewhere in these comments, many stakeholders have concerns about the adequacy of ADI national percentile rankings in determining the level of need of beneficiaries, particularly in densely populated, high-cost areas with stark disparities that are not captured at the census block group level. Relying heavily on ADI national percentile rankings to inform equity initiatives may further disadvantage underserved populations in urban areas, given that the index is not adjusted for geographic differences in cost of living. In the 2016 study CMS cites in the proposed rule to support the use of ADI, researchers did not use the ADI national percentiles and rankings as CMS proposes, but they recalibrated the ADI rankings at the regional and local level, finding the strongest correlations when using the most local adjustments. CMS should identify and implement changes to the ADI to mitigate the shortcomings of relying on ADI national percentile rankings. NAACOS urges CMS to thoughtfully consider these concerns and explore using an adjusted ADI that reflects geographic price differences as well as incorporating additional metrics such as life expectancy.

Ideally, when adequate data sources become available, risk factors-based scores should be informed by individual beneficiary-level social risk factors (SRFs). Patient-reported SRF data provides the most accurate picture of beneficiary needs. While we currently do not have robust data sources for beneficiary-level SRFs, NAACOS urges CMS to explore strategies to collect SRF data and eventually incorporate SRFs into the agency’s equity-focused initiatives in order to most accurately identify the levels of need for each individual beneficiary.

Duration

CMS proposes to provide AIPs for the first two years of the ACO’s agreement period and to allow the ACO to spend the funds over the duration of the entire five-year agreement period. NAACOS supports this proposal as it provides ample time for ACOs to use the funds and invest in sustainable initiatives while ensuring the funds are used promptly and appropriately to impact beneficiaries’ care.

Compliance and Monitoring

Public Reporting and Monitoring of Spend Plan

CMS proposes to require that ACOs publicly report their spend plans as well as actual spending of AIPs, which CMS will monitor for appropriate use. NAACOS supports this proposal as it ensures program transparency and leverages the public reporting webpage already required for MSSP. We ask that CMS provide adequate guidance so that ACOs can report in the appropriate format, and that the agency seek feedback from ACOs when developing the standardized reporting format to ensure minimal burden.

Monitoring for Changes in ACO Experience with Risk and ACO Revenue

CMS also proposes to monitor for changes in the ACO participant list that may cause an ACO to become high revenue or experienced with performance-based risk Medicare ACO initiatives, as defined by CMS, during the course of the agreement period. As proposed, CMS would immediately cease payments upon changes in eligibility, and if the ACO did not remove participants that caused it to become high revenue and/or experienced within a timeframe specified by the agency, CMS would terminate AIPs and require the ACO to repay all AIPs it had received, including spent and unspent funds. As previously discussed, NAACOS sees the proposed eligibility criteria as overly restrictive and this will likely exclude many providers from participating, including key provider types the agency wants to bring into the program. Given these concerns, we strongly encourage CMS to take a more nuanced approach and consider the ACO’s specific circumstances for becoming ineligible for AIPs when determining remedial actions. For example, if an ACO adds a CAH to its participant list and subsequently becomes high revenue, CMS could cease future payments of AIPs but should not require payback of disbursed funds to avoid penalizing ACOs for bringing in safety net providers. CMS could also look at what the AIPs were used for in determining which funds must be repaid. In the case that spent funds were invested in patient care or infrastructure that has a continuing benefit to Medicare providers and/or beneficiaries, CMS should only require repayment of unspent funds. We urge CMS to expand the eligibility criteria for AIPs and, at a minimum, consider a more fair and appropriate approach to compliance policies and remedial actions.

Termination of AIPs

CMS proposes that the agency may terminate an ACO’s receipt of AIPs if the ACO fails to comply with AIP requirements or meets any grounds for termination under § 425.218(b), and that it may immediately terminate an ACO’s AIPs without taking pre-termination actions set forth in § 425.216 in cases of serious noncompliance or when the ACO’s actions pose risk of harm to beneficiaries. NAACOS supports this proposal as it ensures program integrity and appropriate protections for beneficiaries.

Recoupment

\Similar to AIM, CMS proposes to recoup AIPs from any shared savings earned by the ACO in any performance year, including subsequent agreement periods, until CMS has recouped all AIPs. CMS notes that if an ACO does not earn shared savings in its agreement period or a renewed agreement period, CMS would not recoup any of the AIPs. NAACOS supports the proposal to only recoup AIPs from shared savings and to not require payback from ACOs that do not earn shared savings. We encourage CMS to consider recouping AIPs from a portion of the ACO’s earned shared savings each year rather than any shared savings earned in any performance year. We know that it takes time for new ACOs to begin realizing savings and if CMS recoups AIPs from 100 percent of shared savings earned, many ACOs may not receive shared savings payments for a significant period of time, which could discourage continued participation. Annual shared savings payments are used to reinvest in the ACO and to fund sustained initiatives, such as quality improvement activities, that help the ACO continue to grow and be successful. While the receipt of upfront payments will help stand up initial ACO infrastructure and activities, ongoing funding is crucial. NAACOS recommends CMS recoup AIPs from a portion of the shared savings earned by the ACO so the ACO can fund ongoing initiatives. For example, for an ACO participating in Basic Level A with a 40 percent shared savings rate, CMS could recoup AIPs from 20 percent of any savings and allow the ACO to keep the other 20 percent. While this will likely extend the overall recoupment period, it will also provide more continual and sustainable funding for these ACOs, making them more likely to continue participation in MSSP and enabling them to develop more sophisticated ACO capabilities and eventually continue to more advanced levels of risk.

NAACOS also encourages CMS to consider a reduced repayment amount for ACOs serving high proportions of underserved beneficiaries to acknowledge the additional funding required to meaningfully address inequities. For example, CMS could scale the total amount required to be recouped based on the ACO beneficiaries’ risk-factors based scores. ACOs with a majority of assigned beneficiaries with higher risk-factors based scores would have the greatest amount (i.e., 50 percent) of AIPs forgiven by CMS. By tying recoupment policies to equity goals, CMS could further incentivize the expansion of accountable care into underserved communities.

In this section, CMS also proposes that if an ACO terminates its participation during an agreement period in which it received an AIP, the ACO would be required to repay all AIPs received, whether spent or unspent. This approach is overly punitive and does not account for either the reasons for which the ACOs elects to terminate participation or how the funds were used. It is understandable that CMS should reserve the right to require repayment to protect the Trust Fund and program integrity, but CMS should avoid imposing a termination penalty indiscriminately for all ACOs that receive AIPs. NAACOS urges CMS to consider the ACO’s circumstances and timing of termination, in addition to the investments made with the funds before determining the amount of funds to be repaid. Given the complexities of the health care system today, there are many reasons that an ACO may have to terminate participation without the direct intention of avoiding repayment of AIPs. Additionally, spent funds that went into certain investments may continue to benefit the Medicare program and should not be clawed back. For example, if an ACO spent AIPs on electronic health record (EHR) upgrades in the initial years of the participation agreement but had to terminate in year four or five, those investments would continue to benefit Medicare beneficiaries and providers even absent the ACO’s continued participation in MSSP. We recommend CMS revise the proposed recoupment policies to take a more thoughtful and fair approach.

Pathways to Success Glidepath to Risk

NAACOS supports CMS’s proposals to rebalance the risk progression required for ACOs. These proposals will provide additional time in upside-only models and allow ACOs to gain experience before being required to assume risk and therefore attract new participants to the program. However, we are disappointed the high/low revenue distinction remains in place, and we urge CMS to eliminate this arbitrary distinction to ensure all vulnerable providers have a reasonable progression to risk.

ACOs Inexperienced with Risk

CMS proposes to provide ACOs inexperienced with performance-based risk with seven years of participation in the program before being required to take on risk in the eighth year. CMS also discusses a proposal that would allow ACOs inexperienced with performance-based risk who are also low revenue up to 12 years in upside-only models, requiring risk in the thirteenth year.

NAACOS supports providing additional time in upside-only models and applauds CMS for making a more balanced and appropriate onramp to assuming risk. Making these changes will attract new participants to the program after a plateau in growth following the finalization of Pathways to Success policies. However, we urge CMS to alter its current proposals and apply the same policy across all ACOs. Specifically, we urge CMS to eliminate the high/low revenue distinction to ensure all vulnerable providers, such as rural and safety net providers, have a reasonable progression to risk. Evaluations show that ACOs with FQHCs, RHCs, and CAHs as participants will be qualified as high revenue and therefore would be permitted less time in upside-only models as currently proposed. In 2020, 71% of low-revenue ACOs did not include a FQHC, RHC or CAH; conversely, 46% of high revenue ACOs included 5 or more FQHCs, RHCs, or CAHs. The chart below further demonstrates that high revenue ACOs tend to include these providers more than low-revenue ACOs.

|

% ACOs including these providers

|

Critical Access Hospital

|

Federally Qualified Health Center

|

Rural Health Clinic

|

|

High Revenue

|

37.2%

|

27.7%

|

49.0%

|

|

Low Revenue

|

3.8%

|

15.0%

|

16.2%

|

CMS should instead consider alternative approaches, such as evaluating the demographics of the population served by an ACO. The high/low revenue status is arbitrary and leaves out the very ACOs CMS is trying to attract to the program.

Additionally, CMS should reconsider approaches for determining the experience of the ACO. For example, providers that have participated in the program previously but had a break in participation are considered experienced. This may not be appropriate for providers who had a significant break in participation.

Finally, we support CMS’s proposals to amend the definition of performance-based risk Medicare ACO initiative to include only Levels C through E of the Basic Track. Making this change to the definition of performance-based risk Medicare ACO initiative provides a more appropriate reflection of whether an ACO actually has participated in a risk-based model.

Enhanced Track Optional

We applaud CMS for proposing to make the Enhanced Track optional for all ACOs, allowing ACOs to continue to participate in the Basic Track Level E indefinitely. ACOs that choose this level of risk/reward are still contributing greatly to the Trust Fund and assuming substantial levels of risk. This policy change, if finalized, will contribute to the long-term success of the model.

ACOs Currently Participating in Basic Track Levels A, B

Beginning on January 1, 2023, CMS proposes to allow ACOs currently participating in Basic Track Level A or B the option to remain in the upside-only Track for the duration of their agreement period. NAACOS strongly supports this option. CMS has also clarified that ACOs can choose to voluntarily move to risk if they elect this option. These proposals give ACOs the flexibility needed to be successful in the program and will allow more ACOs to stay in the program and gain experience which will yield to higher savings for CMS. When evaluating performance results for ACOs over time, we see that more experienced ACOs have done better at saving Medicare money. Eighty percent of ACOs who started in 2012, 2013, or 2014 earned shared savings in 2020, compared to 59 percent of ACOs who started in 2018, 2019, or 2020. ACOs that started in 2012 or 2013 and earned shared savings netted an average of $7.6 million each to the Medicare Trust Fund, compared to ACOs that started in 2019 or 2020 which netted an average of $4.6 million. These policies help to support ACOs in their continued efforts to improve quality and lower costs for CMS.

Beneficiary Assignment

Definition of Primary Care Services Used in Assignment

CMS proposes to revise the definition of primary care services used to assign beneficiaries to ACOs to include additional codes and to make a technical change to the definition. NAACOS supports proposals to:

- Add HCPCS codes for prolonged nursing facility services (GXXX2) and prolonged home services (GXXX3). As CMS notes, these codes reflect the provision of services beyond the total time for codes currently included in the MSSP assignment list.

- Add HCPCS codes for chronic pain management (CPM) (GYYY1 and GYYY2). CMS states that CPM services are intended to be analogous to chronic care management (CCM) and principal care management (PCM) services, which are already included in MSSP assignment. Since CPM services have not been previously payable under Medicare, we encourage CMS to monitor billing to ensure that they adequately reflect primary care services used in assignment.

- Remove the reference to “place of service modifier 12” from the description for E/M home services (CPT codes 99341 through 33950) to reflect changes to the guidelines that expand the codes to include services provided in places of service other than a private residence.

Using CMS Certification Numbers in Assignment

CMS proposes to implement new policies for using CMS Certification Numbers (CCNs) in MSSP beneficiary assignment for ACOs that have selected preliminary prospective assignment with retrospective reconciliation. Specifically, CMS would determine the CCNs enrolled under an ACO participant TIN during the performance year and include newly enrolled CCNs for purposes of program operations, including beneficiary assignment. Additionally, CMS would develop a mechanism for reporting to ACOs all CCNs identified as participants in the ACO at the start of each performance year and on a periodic basis during the performance year. NAACOS supports these proposed policies as they create a more accurate assignment list for ACOs who have participant providers that are FQHCs, RHCs, Electing Teaching Amendment (ETA) hospitals, and CAHs. Given the potential impacts of these policies on various aspects of program operations such as benchmarking, quality reporting, and eligibility for AIPs, we encourage CMS to monitor the effects of these new policies for any unintended consequences to avoid penalizing ACOs for bringing more safety net providers into the program. We also recommend CMS solicit feedback from ACOs on the reporting mechanism to ensure that ACOs affected by these policies have a clear understanding of assignment list changes during the performance year and how those changes affect program operations.

Quality Changes

NAACOS is pleased to see CMS taking steps to improve the quality performance standard requirements for ACOs, which will allow more ACOs to share in savings they may generate for CMS. However, we are disappointed that CMS continues to utilize the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program to assess ACO quality and does not address the significant challenges that remain with the electronic Clinical Quality Measure (eCQM) reporting requirements for ACOs. We urge CMS to take steps to address these issues and remove the all-payer requirements associated with eCQM/MIPS CQM reporting for ACOs.

Quality Performance Standard and Shared Savings Rates

CMS proposes the addition of an alternative quality performance standard that will allow ACOs who fail to meet the prescribed quality performance standard and earn maximum savings, to be eligible to earn a portion of shared savings. Specifically, beginning with PY 2023, if an ACO achieves a quality performance score equal to the 10th percentile or higher on at least one of the four outcome measures in the APM Performance Pathway (APP) measure set, the ACO would share in savings at a lower rate that reflects the ACO’s quality performance score. The ACO’s final sharing rate would be a scaled by multiplying the maximum sharing rate for the ACO’s track/level by the ACO’s quality performance score.

NAACOS strongly supports this policy proposal as a more balanced approach to determining how quality scores contribute to shared savings opportunities for ACOs. The proposed approach allows for ACOs to have more reasonable quality performance targets and removes the all-or-nothing approach CMS is currently using, which is overly punitive and could cause a large portion of ACOs to miss out on shared savings opportunities. We applaud CMS for being responsive to NAACOS’ concerns with the current approach and proposing this alternative. Additionally, tying the alternative quality performance standard to individual measure benchmarks provides more predictability, as these benchmarks are known in advance of the performance period.

However, we continue to have concerns with CMS tying the higher quality performance standard amount to all MIPS quality performance category scores, as this does not allow ACOs to know what the threshold amount is in advance of the performance period and makes inappropriate comparisons between ACO and MIPS clinicians’ quality scores. As an example, ACOs are not given a choice of measures to report on, while MIPS clinicians can choose from many measures, allowing them to pick the measures they will perform highest on. In addition, there are different case minimums and attribution approaches for MIPS clinicians reporting the same measures and many MIPS clinicians qualify for program exceptions altogether. This policy could also cause CMS to reopen ACO financial determinations if MIPS errors are identified, as further described in our comments below. Therefore, we urge CMS to reconsider tying the higher ACO quality performance standard to MIPS clinicians’ quality performance category scores. If CMS continues to rely on the APP for ACO quality assessments, at a minimum the agency should establish ACO quality targets that are known in advance, such as individual measure benchmarks as has been proposed for the lower quality standard.

Quality Performance Standard Historic Scores

CMS notes it erroneously published weighted scores for MIPS quality performance category percentile scores for 2018 and 2019 in the 2022 PFS proposed and final rules. The corrected historic scores for 2018 and 2019 published in this rule are significantly lower than previously published. We call on CMS to provide further explanation of what “weighted scores” were published and the reason for the error. This further emphasizes the need for CMS to provide additional transparency around how the quality performance standard threshold is calculated. Specifically, we urge CMS to begin publishing MIPS quality performance category scores in the Public Use Files (PUF) annually so that ACOs and other stakeholders can reproduce the calculations and have more transparency around how the performance standard is established.

We continue to believe tying ACO quality performance thresholds to MIPS scores is inappropriate and makes unfair comparisons. Should CMS continue with this approach, there must be additional transparency provided to ACOs and the public as millions of dollars are at stake by connecting MIPS scores to CMS’s largest and most successful value-based program, the MSSP.

MIPS Errors and ACO Financial Determinations

MSSP shared savings and loss calculations are tied to whether an ACO meets the established quality performance standard, which is developed based on MIPS quality scores. In this rule, CMS notes that it has sole discretion to make corrections to a prior performance year’s MSSP ACO financial determinations as a result of corrections made to MIPS quality performance category scores.

Typically, CMS provides MSSP financial reconciliation reports in August of the year following the performance year, with payments to ACOs initiated in September. The timeline for conducting MIPS targeted review may extend past the date CMS issues financial reconciliation reports for ACOs. Accordingly, CMS may learn of MIPS quality performance calculation errors after MSSP initial financial performance determinations are issued. CMS notes it is considering an approach in which CMS would reopen initial MSSP financial determinations to account for changes to MIPS quality performance scores. Reopening these determinations could affect whether an ACO is eligible for shared savings and the amount of shared savings or losses. In these cases, CMS notes it would potentially adjust future financial performance determinations to account for changes as a result of MIPS quality score changes. This approach would not alter the current requirement that ACOs repay shared losses within 90 days after notification of the initial determination of shared losses.

This inherent and unavoidable problem reflects the need for a different approach. We continue to believe tying ACO quality performance thresholds to MIPS scores is inappropriate and makes unfair comparisons, and we urge CMS to adopt a different approach that does not tie MSSP quality performance determinations to MIPS quality performance scores. Should CMS continue with this approach, it should only reopen ACO financial determinations if the MIPS error would result in a change that holds the ACO harmless. To expect ACOs to claw back savings from participants after the funds have already been distributed is unreasonable and not practical. At a minimum, CMS must place a limit on the length of time that can pass before retroactively changing ACO financial determinations, such as 12 months.

Shared Losses and Quality Scores – Enhanced Track Participants

CMS proposes to alter the shared loss rate calculation for Enhanced Track ACOs that do not meet the quality performance standard threshold. Beginning in PY 2023, an ACO that meets the existing quality performance standard or that meets the new alternative standard would have shared losses scaled to one minus the product of the maximum sharing rate for the Enhanced Track (75 percent) and the ACO’s quality performance score. NAACOS supports this more balanced approach and urges CMS to finalize this proposal. This will provide a more reasonable loss sharing rate to ACOs providing high quality care to Medicare patients.

Health Equity Bonus Points for Qualifying ACOs

Beginning in PY 2023, CMS proposes to establish a health equity adjustment that would award bonus points to the quality performance score for ACOs delivering high quality care to underserved populations. The bonus points are only available only to ACOs reporting eCQMs or MIPS CQMs and up to 10 health equity bonus points would be added to the total quality score. The number of bonus points earned would be based on the ACO’s performance on quality measures and the population served by the ACO, specifically ADI national percentile rank of 85 or higher and dual eligible status.

While NAACOS supports the concept of this bonus opportunity, we do not think this proposal goes far enough to eliminate the negative consequences of the all-payer requirement associated with eCQM reporting. Additionally, we believe CMS should go a step further in providing incentives to ACOs working to address health inequities. Specifically, we believe CMS should instead first focus on promoting better data collection to support this work. It is critical to begin collecting race and ethnicity data and SRF data in a standardized way in order to be able to begin to deploy more targeted care coordination and improvement strategies to close equity gaps. The U.S. Census Bureau or other national standard could be used, as one example, for CMS to begin measuring this critical information. Caution should be used when considering mandating requirements that would necessitate costly EHR upgrades and adjustments. As such, incentives could be put in place to allow ACOs time to incorporate this data collection and provide financial incentives to those who are ready to move forward with adoption. As an example, quality bonus points could be awarded to those ACOs who are ready to begin reporting this data.

Stratifying quality measures by SRFs would also allow ACOs to target tailored interventions designed to have the most meaningful impact on underserved populations. In this way, ACOs can address health inequities existing within their patient populations. There are many quality measures which CMS currently considers to be “topped out,” meaning performance is high among most reporting the measures; however, these measures may show additional room for improvement when stratified by SRFs such as income level, as an example. These efforts to address health inequities through quality measurement must be coupled with other efforts to support ACOs in addressing health equity. Equity initiatives require significant upfront investment to be effective, and, therefore, ACOs require additional flexibility and resources to be able to address these concerns with their patient populations.

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) has begun to stratify a subset of quality measures by race and ethnicity to identify areas for improvement. CMS should begin to identify a subset of ACO quality measures that could be stratified by race and ethnicity, or SRFs. To do this successfully, however, there first must be accurate and complete data on race and ethnicity available to ACOs. CMS could also look to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) efforts in this space, as FQHCs are currently required to report data in this manner as part of the Uniform Data System (UDS) Resources Requirements. Specifically, hypertension data in the UDS are reported by race and ethnicity which allows HRSA to identify potential health disparities and develop innovative solutions to address them. From 2016 to 2018, the UDS shows that among the adult HRSA Health Centers (HCs) population, Asians, Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites, and individuals who reported multiple races had the highest percentages of controlled hypertension. Conversely, non-Hispanic Blacks and Native Hawaiians had the lowest percentages of controlled hypertension. Reporting data in this way would allow ACOs to identify possible disparities and improve equity through targeted care coordination and improvement strategies.

CMS should consider providing incentives for improving quality scores for subpopulations identified as having lower performance based on race and ethnicity categorizations. This could be done through bonus or improvement points added to an ACO’s final quality score. This will necessitate relying on complete and accurate baseline data and is therefore a more advanced stage policy recommendation. Therefore, bonus points could be awarded initially to an ACO for reporting race and ethnicity data accompanied with quality data. As accurate baselines develop, improvement points could be awarded for improvement within specific subcategories. As an example, HRSA currently provides performance-based supplementary funding through its Quality Improvement Awards to HCs that made at least a 10 percent improvement toward stated targets from prior years in at least one or more racial/ethnic groups. In addition, current measures and benchmarks may unfairly affect performance of ACOs with a larger portion of patients with social need. Stratifying subpopulations and incentivizing improvement could help ACOs invest in resources to make improvements.

Absent these policies, we recommend several changes to the current health equity quality bonus points proposals. First, we urge CMS to expand this bonus opportunity to all ACOs regardless of what reporting method they have chosen. According to CMS, only 12 ACOs elected to report via eCQMs in 2021, therefore this bonus will have limited applicability. Second, we urge CMS to reconsider the use of ADI in determining eligibility for this bonus. As previously discussed in this letter, the use of ADI as proposed may accurately identify some disadvantaged areas, but it does not appear to consistently do so in all types of communities. The ADI uses metrics like rent and income, which are not adjusted for differences in cost of living between different geographic areas. This results in places with high cost of living appearing to be advantaged and places with low cost of living appearing disadvantaged and therefore does not capture disparities in some areas – particularly high-cost urban neighborhoods. For example, most of the census block groups in the South Bronx, which is considered the poorest congressional district in the country have ADI national percentile ranks between 11-40, meaning they fall into the “least disadvantaged” and would not be considered “disadvantaged.”

In the proposed rule, CMS cites a study from 2016 titled, “Integrating Social Determinants of Health With Treatment and Prevention: A New Tool to Assess Local Area Deprivation” as evidence for the use of census block group level analysis. As previously mentioned, this study did not use the ADI as CMS has proposed to use it within the MSSP. Specifically, CMS is proposing to use national rankings and percentiles. Whereas in the study cited, the researchers recalibrated ADI rankings at the regional and local level (10 km, 20 km, and 30km from the zip code tabulation area) and found higher correlations between hospitalization rates when using the most local of these. The study states, “These findings support the need for locally sensitive relative deprivation measures; national and regional approaches do not appear to properly model the potential impact of area deprivation on health outcomes in a smaller study area.” Given these issues with the ADI national percentile rankings, we suggest that CMS consider an alternative such as use of an absolute measure like life expectancy as an example, or identify and implement changes to the ADI to address these issues. Additionally, CMS may want to consider different metrics or calibration approaches for rural vs. urban areas. We also oppose the use of the performance scaler, as it does not achieve CMS’s goal to reward ACOs that provide high-quality care to underserved populations, as an ACO with a good overall quality score may or may not be providing high quality care to underserved populations. Instead, we urge CMS to focus on promoting better data collection to support this work, as described in this letter.

MSSP Quality Measure Changes

Data Completeness

CMS does not propose changes to the MSSP quality measure sets for PY 2023. However, CMS proposes to increase the quality data completeness standard from 70 percent to 75 percent in 2024 for MIPS policies, which would also apply to ACOs reporting eCQMs or MIPS CQMs. NAACOS opposes any increases in the data completeness standard for ACOs and asks CMS to consider what its goals for this requirement are, particularly in the context of ACOs reporting eCQMs or MIPS CQMs. CMS seeks to hold ACOs, clinicians, and groups to a bar higher than any other CMS quality program. Health plans are required to report on a sample of patients for each of the measures that require clinical data beyond administrative claims in the Medicare Part C and D Star ratings as are hospitals that must abstract clinical data on a sample of patients. None of these sample sizes, which are based on the number of plan participants or individuals admitted to the hospital for a specific diagnosis or procedure, come close to the current 70 percent data completeness requirement in MIPS. CMS has not sufficiently justified why a larger sample is required when smaller sample sizes are determined to provide sufficient information on which CMS and others can make informed decisions on the quality of care delivered for health plans and hospitals.

As the percent of data completeness increases, ACOs will also encounter further challenges around ensuring that they can accurately and reliably capture all eligible patients and encounters for each of the measures. Specifically, there are some specialties (e.g., radiology, gastroenterology) that provide services across multiple sites using the same NPI/TIN; however, it should not be assumed that these sites of service participate in MIPS, have agreements in place to share data with the ACO, and/or require significant coordination, time, and resources to extract the data from an EHR that is not linked with the ACO’s systems.

Potential Future Inclusion of Measures on Social Drivers of Health

CMS also seeks comment on the potential future inclusion of two new measures in the MSSP quality measure set, Screening for Social Drivers of Health and Screen Positive Rate for Social Drivers of Health. CMS also seeks comment on the potential future question for the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) for MIPS Survey that addresses health disparities and patient experience with discrimination, as well as price transparency.

NAACOS supports CMS’s efforts to improve health inequities and incentivize screenings for SDOH. However, CMS must recognize the current state of this work and first start with efforts around data standardization and providing pay-for-reporting if incorporating any such measures in performance-based programs like MSSP. This work is iterative, and we are still in the early phases; therefore, CMS should limit any measures on SDOH screening to testing/pilots within ACOs that would allow more learning to happen in this space. While screening for SDOH is an important first step, this must ultimately be coupled with efforts to address issues identified by the screening. To screen without also providing follow-up can do harm to the patient. CMS should also allow for more standardization to occur and to gather data and learn about workflow issues that occur with screenings during a testing/pilot phase where any screening measure would be pay-for-reporting and would not dictate which screening tool was used or how it was implemented. As an example, some ACOs may choose to do the screening as part of an office visit while others may instead find more value in providing an online screening tool that is completed outside an office visit.

Regardless, screening measures should be used as one tool in a larger plan to address health inequities and provide high value care to underserved communities. NAACOS provides more detailed recommendations on this topic on our website. Finally, NAACOS has concerns with the Screen Positive Rate for Social Drivers of Health measure, as the measure does not provide information regarding follow-up on a positive screen and therefore does not provide any real insights into the provision of care provided by the ACO.

Measure Specification Changes

Finally, in terms of measure specification changes, NAACOS opposes any broadening of the denominators for eCQMs to include additional specialties. When applied at the ACO level, this creates an inappropriate evaluation of ACOs. Detailed comments on individual measures are included below.

Diabetes: Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Poor Control (>9 percent) (eCQM)

NAACOS does not support the expansion of the denominator to include additional specialties. We believe that this measure should be solely focused on primary care, particularly when it is used to assess the quality of care provided by an ACO. As outlined in our comments around the proposed increase to data completeness, requiring the identification of eligible patients across all practices regardless of payer is challenging given the number of clinics, sites of service, and specialties that have established relationships with the ACO. To add additional specialties to this measure increases the complexity of identifying the eligible patient population and we question whether this expansion, at the ACO level, contributes useful information around the quality of care. We urge CMS to consider a different attribution approach such as limiting data to all Medicare patients when it is reported at the ACO level.

Preventive Care and Screening: Screening for Depression and Follow-Up Plan (eCQM)

NAACOS appreciates the ongoing efforts to further clarify the intent and specifications of this measure. We support the revisions to the guidance, particularly allowing follow-up documentation to occur up to 48 hours after the encounter.

Quality Benchmark Changes

For PYs 2022 and 2023 CMS proposes to use flat percentage benchmarks for two measures. This policy is retroactive for 2022. The measures are: Preventative Care and Screening: Tobacco Use: Screening and Cessation Intervention (Quality ID# 226) and the Preventive Care and Screening: Screening for Depression and Follow-up Plan (Quality ID 134). As a result, ACOs would be scored on eight out of 10 CMS Web Interface measures for the 2022. This differs from previous policy where CMS finalized ACOs would be scored on seven out of 10 Web Interface measures for 2022.

NAACOS opposes CMS making retroactive policy changes in relation to quality metrics or performance requirements. Making these changes, which will be finalized in November, during the performance year is unfair and ignores how quality improvement efforts are operationalized within ACOs. The same is true for measure specification changes made mid-year. We urge CMS to continue making these measures pay-for-reporting for 2022, as was finalized in the 2022 MPFS rule.

Extending eCQM/MIPS CQM Reporting Incentives

CMS previously finalized incentives for ACOs reporting eCQMs or MIPS CQMs for 2022 and 2023. In this rule, CMS proposes to extend the availability of the reporting incentives through 2024. NAACOS supports the proposed extension of incentives for ACOs reporting eCQMs/MIPS CQMs through 2024. However, we urge CMS to also strengthen incentives for ACOs making the enormous financial and operational commitments to do the work of transitioning to eCQM/MIPS CQM reporting. By proposing an additional, lower quality performance standard for all ACOs in this regulation, CMS is watering down incentives for reporting eCQMs even further. Instead, we urge CMS to provide ACOs reporting eCQMs or MIPS CQMs prior to the 2025 deadline with pay-for-reporting status for all three clinical quality measures included in the APP measure set. As an alternative, CMS could consider providing up-front funding and/or adjustments to financial benchmarks, or an increased savings rate to provide real and substantial funding and incentives for ACOs to do this very expensive and time-consuming work.

NAACOS continues to have concerns with CMS’s timeline to require all ACOs to report eCQMs/MIPS CQMs for all-payer data by 2025. Moving to more digital measurement that is bidirectional and improves clinicians’ ability to improve patient care at the point of care is a laudable goal. However, CMS must have realistic timelines when placing requirements on industry. According to a recent survey of our membership, only 38 percent of ACOs responding said they will be able to report eCQMs in 2025. What’s more, this transition is very costly for many ACOs. Forty-one percent surveyed estimated a cost of $100,000 to $499,000, and 32 percent estimated more than $500,000 to achieve eCQM requirements for the first year of reporting. Further, many vendors continue to tell ACO clients they are unable to support this work at this time.

As a result, CMS should instead look to pilot eCQMs for a subset of ACOs who feel best suited to move forward to identify key challenges and unintended consequences that need to be resolved before moving forward on a program-wide basis. Additionally, CMS should provide incentives for ACOs to do this testing, such as providing pay-for-reporting status for quality measures, upfront funding, adjustments to financial benchmarks, or an increased savings rate to help offset the high costs for doing this work. NAACOS has convened a Digital Quality Measurement Task Force to provide recommendations for technical solutions needed in order for ACOs to be successful in reporting eCQMs, which will be published this fall to provide additional detail in this area.

Financial Methodology

NAACOS is pleased to see CMS propose multiple changes which overall will create fairer, more accurate financial benchmarks for ACOs. NAACOS has long advocated for several of these policies. In particular, we appreciate that CMS has responded to requests to address the cap on risk score growth over an ACO’s five-year agreement period and the “rural glitch,” where ACOs no longer benefit from the regional adjustment when lowering the spending of their assigned patients and thus lowering regional spending. While neither of these concerns are solved in this proposed rule, CMS does take steps to mitigate the negative effects of both policies.

We greatly appreciate that CMS acknowledges the “ratchet effect” with proposals to update benchmarks using an Accountable Care Prospective Trend and adding back ACOs’ shared savings when calculating the benchmark for new agreement periods. Overall, NAACOS believes the net impact of the proposed rule will help encourage ACO participation, although we have concerns about the unintended consequences of some of the proposed changes and offer mitigating solutions below.

NAACOS requests that CMS allow current ACOs to opt into certain financial changes beginning in 2024. All of the proposed changes to MSSP’s financial methodology are limited to new agreements that start in 2024. Of the current 483 MSSP ACOs, 206 (43 percent) started new agreements in 2022 and would have to wait until 2027 to see any of the proposed changes. Few ACOs would benefit from the proposed changes and existing ACOs would have to go through the onerous process of early renewing. To encourage ACO growth and recognize challenges existing ACOs are facing with the financial methodology polices, CMS should grant current ACOs the option to opt into these changes sooner. CMS allowed ACOs to move into the Pathways structure in 2019 by simply modifying existing contracts; we feel CMS could make a similar allowance for these policies, if finalized.

Incorporating a Prospective, External Factor in Growth Rates Used to Update the Historical Benchmark

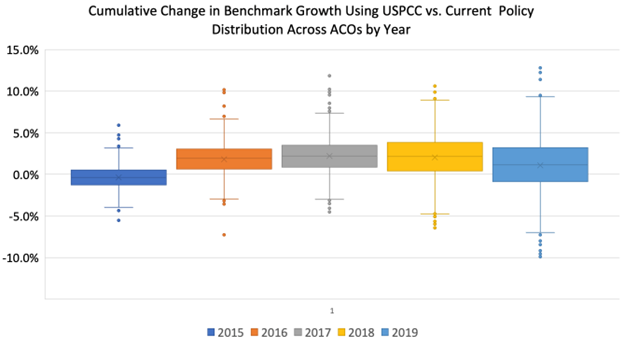

CMS proposes to add an “Accountable Care Prospective Trend” (ACPT) to update historical benchmarks. This would count as one-third of the trend with the existing national-regional blended growth rate comprising the other two-thirds. The ACPT would be based on United States Per Capita Cost (USPCC), projected by the CMS Actuary annually. CMS proposes to set 5-year per capita projections for each enrollment type at the start of an ACO’s agreement period. CMS retains discretion to adjust the weight of the ACPT if actual spending significantly deviates from projections.

Because there is significant variation in regional spending growth, NAACOS is concerned that use of CMS’s proposed ACPT will harm ACOs in regions where spending growth exceeds the ACPT because those ACOs will have lower benchmarks over time compared with current policy. Rather than its proposed policy, NAACOS urges CMS to keep its current two-way trend that uses a blend of national and regional spending but recommends two changes: CMS (1) use the ACPT as the national component of the trend adjustment, rather than observed national FFS spending and (2) remove ACO-assigned beneficiaries from the regional comparison group, negating the effect of ACOs’ savings on the regional trend. These changes would allow CMS to meet all of its goals, including moving toward administrative benchmarking and minimizing the unintended consequences of harming nearly a third of ACOs that we outline below. This both takes the first step of using projected administrative trends in benchmarking while removing the inequities associated with including an ACO’s beneficiaries in its regional trend.

If CMS does finalize the proposed three-way trend update, NAACOS strongly urges that sufficient guardrails are put in place to protect ACOs who would see lower benchmarks because of the ACPT. Specifically, we recommend CMS set ACOs’ historic benchmark at the higher of the proposed three-way trend adjustment or the current two-way trend adjustment. We further recommend CMS consider alternative proposals to mitigate negative impacts of the ACPT such as basing it on regional spending, rather than national. Because there is significant variation in regional spending growth, the use of a national trend factor will benefit ACOs in regions with slower spending growth and reduce benchmarks for ACOs in regions with higher spending growth. As a result, efficient, low-cost providers, including ACOs, who operate in regions where spending exceeds the ACPT will be harmed by having their already low spending targets reduced over time. While we appreciate CMS’s efforts to create a stable, more predictable update factor in MSSP benchmarks, additional adjustments are needed to account for regional variations. CMS acknowledges the need to consider regional variation in its request for information (RFI) on administrative benchmarks included in the proposed rule. Yet, the agency does not account for regional variation with the proposal to incorporate the ACPT.

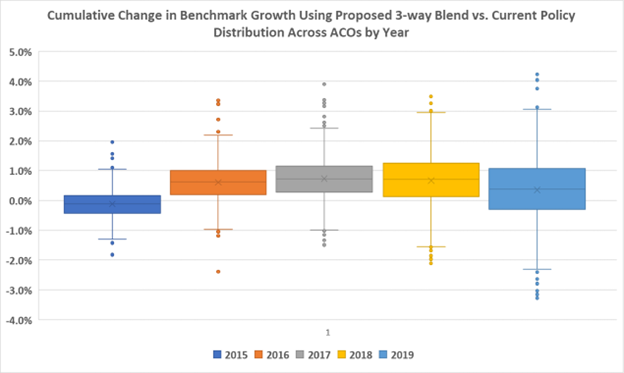

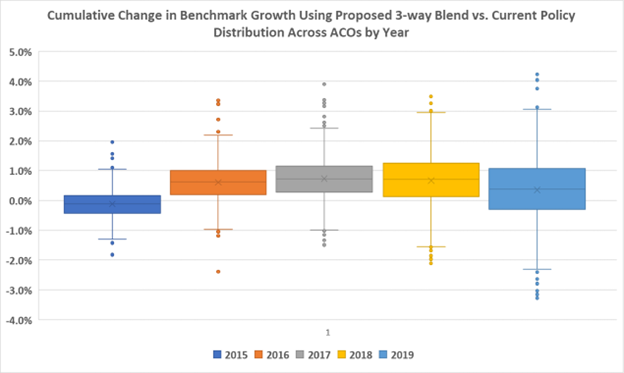

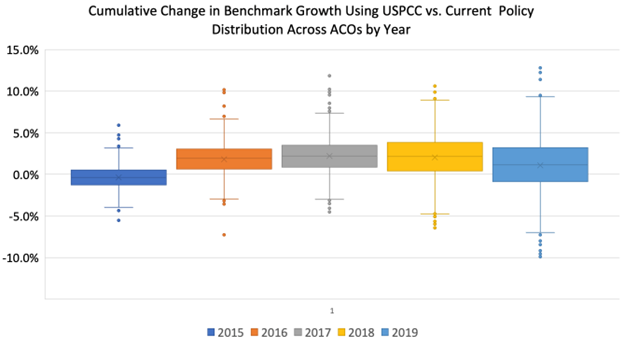

Using published USPCC rates from 2014-2019, the Institute for Accountable Care modeled the impact of the proposed policy for 2018 MSSP ACOs. Overall, a significant number of ACOs would be negatively impacted by the proposed three-way trend with the ACPT. Specifically, 66 percent of ACOs would benefit from using the projected “administrative” trend while 34 percent would face lower benchmarks over the five-year period (see Graphic 1 below). In fact, nearly 5 percent of ACOs would see benchmarks fall by 2 percent or more by the end of their five-year agreement. By CMS’s own projections in the proposed rule, 62 percent of ACOs could see a higher benchmark under the three-way trend with ACPT. Presumably, 38 percent of ACOs would see a lower benchmark.

Graphic 1: Cumulative Impact of a One-Third Administrative Benchmark

Ultimately, the national ACO spending trend is not reflective of the spending in an ACO’s region, and when an ACO’s regional trend is lower than the USPCC, the ACO would be negatively impacted. Accordingly, there is geographic variation in the impact of the ACPT. ACOs in states with low spending growth – such as California and New York – would be punished. The experience of ACOs in Florida, for example, would be very different. ACOs should not be punished if they operate in regions with spending growth below that of national inflation. The differences between regional and national trends amplifies over time rather than regressing to the mean. Analysis of the differences between regional and national trends from 2015 to 2020, highlighted over twenty-five percent of counties with more than three thousand assignable Medicare beneficiaries will be on one side of the national trend (either positive or negative) for all five years. Additionally, we find growing polarization over time, with fewer counties matching the average national trend. Accordingly, if an ACO was in a region where spending growth falls below that of the USPCC, they would receive smaller update factors under CMS’s proposed use of the ACPT. If CMS were to rely purely on the ACPT as proposed it would hurt low-cost, efficient providers and counter its goal of 100 percent ACO participation.

If the ACPT is added to create a three-way trend, the national contribution to the trend increases for most ACOs. Nearly all ACOs are minority contributors to the performance of their region compared to national trends. The one-third inclusion of a national-only ACPT would make every ACO with 25 percent market share or more graded at 50 percent national trend. An ACO that only makes up 5 percent of its market would be graded on over one-third national trend. This measurement makes an ACO responsible for more of its market than it can influence and would serve as a powerful incentive to consolidate.

NAACOS believes a policy that negatively impacts a third of ACOs should be reexamined. As CMS’s stated goal is to grow the ACO program, such policies could run counter to that goal by causing ACOs to leave the program. To mitigate these negative consequences, NAACOS recommends that if CMS finalizes its proposal that it use the higher of the proposed three-way trend adjustment or the current two-way trend adjustment. We further recommend CMS consider alternative proposals to mitigate negative impacts of the ACPT such as basing it on regional spending or using it to replace the national trend.

Using the more favorable of the three-way trend and the two-way trend

For ACOs that produce shared losses, CMS proposes to recalculate an updated historical benchmark using the two-way trend when it would reduce the shared losses. NAACOS appreciates this proposal, but given our concerns stated above, this guardrail should be expanded if CMS finalizes the proposed three-way trend. Our request is to give ACOs the more favorable benchmark of either the current two-way or proposed three-way trend at or near the start of the performance year. Under the proposed policies, CMS will already calculate the two-way trend, so our request would not place any additional burden on the agency. Instead, our request would help ACOs in regions with high spending growth avoid being punished with lower benchmarks, since high regional growth rates can be caused by a host of local market factors (e.g., opening of new tertiary services) beyond an ACO’s control.

Apply an ACPT that is based on regional spending

Since 2017, CMS has incorporated regional spending into the benchmarks, and regional spending was incorporated earlier in an ACO’s agreement beginning in 2019. CMS explained in the June 2016 final rule that this approach would make an ACO’s financial benchmarks “more independent of its historical expenditures and more reflective of FFS spending in its region.” But the ACPT may differ substantially from FFS spending growth in any ACO’s region. NAACOS reiterates its request to use a regional-only trend, which is a better reflection of a local market than a national trend or a blended national-regional trend. Moreover, regional trends would help facilitate alignment between the Medicare Advantage and ACO benchmarking approaches. If CMS moves forward with a prospectively set trend, we strongly recommend the agency use a regional calculation, rather than national. Furthermore, we still believe CMS should remove ACO-assigned beneficiaries from the regional trend component of benchmarks. While CMS declined to make this change in this proposed rule, NAACOS continues to believe that removing ACO patients from any regional adjustments would create a more realistic picture of the spending in an ACO’s region.

Reconsider use of a 5-year ACPT

While the length of the ACPT at 5 years aligns with the MSSP contract, it is beyond the current three-year projections of the USPCC. CMS should consider beginning with a 3-year projection and provide more information on how the ACPT could change over an ACO’s five-year period, including what would trigger the change and factors contributing to the decision. CMS states it reserves the right to change the weight given to the trend, reducing it from a third of the benchmark to a smaller number to account for instances in which the prospectively set trend differs greatly from the actual trend. These unknown adjustments that occur after or during the performance year create uncertainty in the model. In recent years, trend adjustments in the Next Generation ACO Model and Global and Professional Direct Contracting Model during the performance year created great disruption for model participants. While the changes were necessary to account for the historic COVID-19 pandemic, they also caused great uncertainty for model participants. This is counter to the policy objective of a prospectively set trend.

Adjusting ACO Benchmarks to Account for Prior Savings

CMS proposes to account for an ACO’s prior savings generated in the three baseline years when rebasing benchmarks for new agreement periods. Prior savings adjustments would be pro-rated and dependent on whether an ACO has higher or lower spending then their region. Prior savings adjustments will also be capped at the lesser of 5 percent of national per capita FFS expenditures in benchmark year 3 (BY3) for assignable beneficiaries or 50 percent of the pro-rated average per capita savings. For ACOs with spending higher than their region, the prior savings adjustment will help offset the negative regional adjustment. For ACOS with spending lower than their region, the prior savings adjustment will be at least as much as the positive regional adjustment.

NAACOS supports CMS’s proposal to account for prior savings when ACO benchmarks are rebased under a new agreement period as this will help CMS retain ACOs in the program. NAACOS appreciates policies that reward strong performance and further incent a transition away from FFS. Based on NAACOS’ analysis, this proposed change will always benefit ACOs, but we feel there are ways to strengthen the policy. First, rather than adjusting ACOs’ earned shared savings by 50 percent, as CMS proposed, the agency should use an ACO’s maximum shared savings rate from their prior agreement period to pro-rate the positive average per capita savings. For example, if an ACO was in the Enhanced Track in the prior agreement, then CMS should pro-rate the prior savings adjustment by 75 percent. CMS proposed a 50 percent scaling factor as a matter of simplicity. However, using an ACOs maximum shared savings rate creates incentive for ACOS to take on greater levels of risk and is consistent with the June 2015 final rule when prior savings adjustments were first implemented.